- Home

- Jr. Greene, James

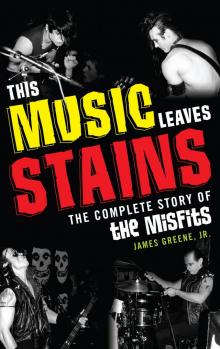

This Music Leaves Stains

This Music Leaves Stains Read online

This Music Leaves Stains

The Complete Story of the Misfits

James Greene Jr.

THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC.

Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK

2013

Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PP, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2013 by James Greene Jr.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Greene, James, Jr., 1979–

This music leaves stains : the complete story of the Misfits / James R. Greene Jr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8108-8437-3 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8438-0 (ebook) 1. Misfits (Musical group) 2. Punk rock musicians—United States—Biography. I. Title.

ML421.M576G74 2013

782.42166092'2—dc23

[B] 2012042761

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For Theodora and James Sr.

Acknowledgments

A sincere and heartfelt thank-you to every person who agreed to be interviewed for this book. Though some ultimately had to be excised from the final pages, every single one of your stories, knowledge, and remembrances helped shape the narrative considerably. I am greatly indebted to you all.

Thank you also to every person who did not agree to be interviewed for this book but conveyed their response in a polite, mannered way that also expressed support and the best of luck with this project. In an age where it is incredibly easy and generally more convenient to simply ignore e-mails, text messages, and other communication from parties unknown, your etiquette touched me even if you were cranking it out on autopilot.

To the handful of individuals who would only agree to aid me for “a nominal fee,” I must say: some of your figures are staggering. If they are indicative of amounts you have received in the past for such projects, bravo. I obviously missed the class on master negotiating you attended.

The following individuals went above and beyond their proverbial calls of duty to help this volume come to fruition: David Adelman, Kathleen Bracken, Chris Bunkley, Ken Chino, Liz Eno, Danny Gamble, Bennett Graff, Christopher Harris, Rollie Hatch, Mark Kennedy, Taylor Knoblock, Brie Koyanagi, Aaron Knowlton, Pete Marshall, Mick Mercer, Rachel Hellion Meyers, Linnéa Olsson, John Piacquadio, Bill Platt, Michael Poley, Lyle Preslar, James Edward Raymond, James Lewis Rumpf, Kevin Salk, Dave Schwartzman, Mike Stax, Bear Steppe, Chopper Steppe, Jim Testa, John L. Welch, Matt Whiting, Joshua Wyatt, and Jay Yuenger.

Thank you of course to the Misfits themselves—even the ones who turned down the opportunity to participate here. Without your fertile subject matter, this book would probably be about something dreadfully boring, like impression-die forging or the history of Quaker Oats.

Extra special thanks to the taco truck at the corner of Stuyvesant Avenue and Broadway in Brooklyn for providing many a platter of pork nachos to help fuel late-night writing sessions. Thank you also to the PepsiCo corporation for the same via their wide variety of Mountain Dew products. Thanks also to the physicians who will help me with the kidney stones I most likely developed from ingesting so much food of this quality.

Preface

The Misfits are a band who have long had a “secret club” aura surrounding them. Like the jaded B-movie criticism vehicle Mystery Science Theater 3000 or the drug-mad writings of Hunter S. Thompson, fans first stumble across this entity and marvel, “I can’t believe something like this exists!” If you feel the connection it is euphoric—finally, a cultural force speaking in a voice previously unheard yet familiar to your own inner monologue. Suddenly you want to know everything about them. You devour information like a rabid dog, swallowing every tidbit you come across.

At fifteen I became aware of the Misfits thanks to an upperclassman in my drawing class named Ed who regularly wore a tattered black shirt bearing the band’s famous blaring white skull mascot. It was vintage, Ed claimed, passed down to him from a cousin or a sibling who had known the band and managed to get the image widely known (despite its lack of red hue) as the Crimson Ghost silkscreened directly on his or her own design-free T-shirt. A logo of the Champion brand on the garment’s sleeve seemed to support my friend’s story (“The Misfits wouldn’t sell a T-shirt with some company’s name on it,” Ed offered, reasonably). At the time I had never heard the Misfits but appreciated that I knew someone who owned something someone relatively famous once touched.

A few months out of high school I was killing time between community college courses at the home of a female friend; to give you some idea of the time period, I believe on that particular afternoon we were commiserating over the sudden gruesome death of Phil Hartman. As we conversed, my friend’s brother began loudly playing a spate of punk rock from his neighboring room. The rapid thumping, muffled ever so slightly by the home’s drywall, was no bother—the Ramones were my bread and butter, after all—but a few minutes in I was struck by the distinct voice cutting through the smashing drums and roaring guitars.

Is that Glenn Danzig?

Like moth to a flame I shuffled into this kid’s room. I don’t remember our verbal exchange—just the surreal moment I picked up the jewel case for Collection II and saw Glenn Danzig’s name clear as day on the sepia-toned back cover. Suddenly it dawned on me.

Oh my God. The guy who sang “Mother” was in a punk band. Like, a really good punk band. This sounds like Elvis and the Ramones and there are goddamn skulls and murder all over this thing.

I was beside myself. Danzig’s eponymous heavy metal band had danced across MTV for a brief moment just a few years before this, but I never bothered to penetrate beyond the surface radio hits. Glenn Danzig’s deal had seemed clear to me: enormous belt buckle, mutton chops, buckets of swagger, deep voice, wanky metal junk. I figured the buck stopped there. Rarely have I ever been so pleased being dead wrong.

The real tipping point was “I Turned into a Martian.” Such a massive amount of catharsis flows through that song for anyone who’s ever identified with being an outcast or an outsider or on the wrong side of normal. In my late teens I was certainly cognizant of the fact it was okay to be different, but that didn’t necessarily always act as a salve when I felt out of place. To hear Danzig just completely own his metamorphosis into an otherworldly creature, to clench it with his fists and turn it around into an anthem of empowerment . . . I mean, that was the most reassuring thing in the world. When he shouts “This world is mine to own!” at the end of the second verse, I always find myself standing up a little straighter.

And the way the Misfits glued the song’s melodies to that grinding riff is just astounding. How often to you ever hear something so forceful, so hard-charging—those first three chords just come barreling out at you like cannon blasts—that’s also so sweet and romantic and (for lack of a better word) epic? There was just no turning back once that song hit my ears. Nearly every Misfit

s song is great, but for my money “I Turned into a Martian” is the greatest.

The next several years were spent absorbing the dark greatness of the Misfits—not just their music, not just their image, but their strange and twisted story. Along the way I saw the band a handful of times during the first five years as a reunited entity, when Michale Graves was filling the unenviable position of Glenn Danzig’s replacement. They were theatrical, a bit showbizzy, but no more so than Danzig’s eponymous band, which I also saw during the same period. I had nothing to judge these experiences against as I was all of four when the Misfits first dissolved in 1983 and I knew no music outside my scratched copy of “Snoopy vs. the Red Baron”; but both experiences offered a fair amount of camp with raw rock n’ roll thrills. In one instance I saw the Misfits at a miniscule club in Daytona Beach called Orbit 3000; the space was so cramped that the crash cymbals sitting above Dr. Chud’s drum kit (an exaggerated set-up that in reality wasn’t that much larger than your average percussion set) were grazing the ceiling. The stage actually collapsed during one of the opening bands that night. Still, the Misfits went on—Michale Graves literally pushing Orbit 3000’s owner out of the way so the band could spread out on the sunken structure and play for the sweaty, packed house. Moments before that, as their ominous intro music played, I remember a backstage light illuminating muscular guitarist Doyle in such a way that his massive shadow spread across a neighboring wall like some horrid two-dimensional monster. A more perfect visual couldn’t have been scripted by Tobe Hooper himself.

A couple days after that particular show, I heard a rumor that the Misfits and the assaulted club owner got into another tussle once the band left Orbit 3000’s stage for the evening, and the end result of that donnybrook was Doyle pitching a security guard through a plate glass window. I tended to believe this story not because Doyle and his brother Jerry were hulking weightlifters with short tempers from New Jersey but because the oppressive heat of central Florida has been known to cause plate glass hurlings before. In 1997 Charles Barkley was arrested in downtown Orlando for chucking some guy through the front window of Phineas Phogg’s just because the victim had tossed some ice in Barkley’s general direction. And this wasn’t even during the regular NBA season—Charles was in town for a friggin’ exhibition game. His Greatness was released on $6,000 bond after spending five hours in jail; as for Doyle, I never heard of any charges one way or another, but interestingly enough the Misfits never again played a show in Daytona Beach.

There was definitely no such violence at the Danzig show I attended circa the same era, and there were also no Misfits songs. That’s what got me in the door. I mean, aside from the thought process “I should see Glenn Danzig in concert just in case this Y2K thing turns out to be real.” Rumors were circulating online that Danzig was closing shows on this particular tour with assorted material from his salad days. Alas, no such luck with the gig I attended. The Internet used to lie a lot more back in the 1990s. It was pretty thrilling to see Glenn nonetheless. His relaxed demeanor between songs conveyed to me that the public image is not always the person and vice versa. For a guy depicted as being so glum all the time he sure was smiling a lot up there (then again, this was the House of Blues, so I’m sure the soup spread backstage was above average).

But I digress. For a long time there was an accepted and set narrative regarding the Misfits, one expertly dug up in the pre-Internet age by devoted historians who understood the aforementioned thirst for knowledge and hoped to quench it. They did a fantastic job, but as the years grew on, this particular fiend needed to know more. Not only because the band was stretching itself in a new form across our new century, but also because so many questions in the oft-repeated tale remained unanswered. It was also stunning that no singular book had yet been devoted to the Misfits, despite the mark they made in punk and the shadow they cast over mainstream rock music. For these reasons, two years ago I decided to buckle down and attempt to author the definitive Misfits tome myself.

Not every mystery regarding this legendary band is solved in the pages that follow (which I suppose is just as well, lest these figures lose their entire sense of intrigue), but light is certainly shed on numerous aspects of the Misfits story that had continued to confuse, and the music is finally given what I hope is considered its full critical shake. It is my sincere hope that my fellow Misfits enthusiasts accept and enjoy this book. It would also be nice if fans of disciple bands took to it as well for any knowledge it imparts.

Hell, so long as this book isn’t burned en masse in any town square or witches’ coven, I’ll be happy. Thank you for your patronage, even if you are only reading this in chunks during occasional visits to the local book store or library.

Stuck in Lodi

1

I could say some nasty things about New Jersey, but once my darling mother said, “Don’t speak unkindly of the dead.” ―Billy Murray, “Over on the Jersey Side”

Of course the Misfits are from New Jersey. No other state could have bred an outfit so great that was ignored for so long. Pop culture’s relative blind eye to the Misfits is very much a microcosm of Jersey itself—despite being perfectly situated between several major metropolitan areas (New York City to the north, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., to the south), the Garden State has long suffered little brother syndrome. For decades the rest of the country has mercilessly taunted New Jersey for being uncultured, odorous, and of no consequence. Never mind that New Jersey is where Thomas Edison did the lion’s share of his groundbreaking scientific and electrical work.[1] Never mind that New Jersey hosts some of our country’s most esteemed institutions of higher learning, including Princeton, William Paterson, and Rutgers. Never mind that saltwater taffy and Campbell’s Soup were both created in New Jersey.[2] This state, to so many, is simply a retainer for the undesirable.

Jersey may shake that stigma yet, but one facet they can’t live down is the number of spooky, ghoulish, and just flat-out bizarre happenings that have occurred within its borders. There was Orson Welles’s mania-inspiring War of the Worlds prank,[3] the still-debated kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby,[4] the crash of the Hindenburg,[5] and the ferocious shark attacks by the so-called Jersey Man-Eater;[6] a handful of motorways like Clinton Road and Shades of Death Road that are said to be festooned with all manner of angry poltergeists,[7] as are a number of structures with apropos names like the Devil’s Tree[8] and the Devil’s Tower;[9] one of history’s most famous cryptids, the Jersey Devil, has allegedly been raising hell in the Pine Barrens since colonial times;[10] numerous odd conglomerations of societal outsiders like the allegedly inbred Jackson Whites[11] and the nature-worshipping Gatherers;[12] and who could forget Suzanne Muldowney, that extremely intense woman who runs around New Jersey performing interpretive dance routines in her homemade Underdog costume.[13] It’s understandable how all this might inspire a few outcast kids to start dressing like zombies and write songs about murder.

Speaking of murder: New Jersey is also noted for its rich mafia history, which dates back to America’s Prohibition era. The Gambino, Genovese, and Lucchese crime families have all had their fingers buried deep in the Garden State at varying times,[14] and the indigenous DeCavalcante family served as the basis for HBO’s wildly popular Sopranos television series.[15] In fact, Lodi’s own Satin Dolls strip club on Route 17 served as the filming location for Tony Soprano’s favorite hangout,[16] the Bada Bing! (Satin Dolls proudly touts this fact in all their current advertising.)[17]

This litany of macabre happenings aside, there is still an all-American charm to New Jersey, thanks to its sprawling, often picturesque suburbs, most of which were first constructed during the 1950s post-war boom. Neighborhood after neighborhood of ranch style homes project safety, comfort, and serenity. Every little borough has its own beloved pizza place, its own quaint town hall, its own ragtag high school football team the whole area gets behind with a fervor. In many ways New Jersey’s assorted townships and villages are as close to

Leave It to Beaver as you can get. To a teenager with dreams of conquering a neighboring metropolis, though, such an environment can be the epitome of boring, regressive, and stifling, breeding a dangerous complacency. Often, the only respite in such a situation is music.

Luckily, New Jersey has a rich and varied musical lineage. Hoboken’s native son Frank Sinatra crooned his way to icon status, redefining cool along the way, in the 1940s and 1950s.[18] Belleville’s Four Seasons are considered by many to be the greatest pop vocal act of all time (and they have the millions in sales to back that assessment up).[19] Although he is usually associated more closely with Asbury Park, the city of Long Branch can claim Bruce Springsteen and his songwriting genius as their own. Jersey City gave the world soul/funk ambassadors Kool & the Gang.[20] Jersey was also the sight of the first live performance by the Velvet Underground, a 1965 gig at Summit High School (for which the influential assembly charged just $2.50 a ticket).[21] And as if those giants weren’t enough, Les Paul, the man who more or less gave birth to rock n’ roll by crafting and marketing one of the world’s first solid-body electric guitars in the 1940s, settled for years in the township of Mahwah until his death in 2009.[22]

From this frothy stew of cultural activity both great and dubious rose the Misfits, founders and pioneers of what many dub “horror punk,” as that strain of music had never been so ghoulish or gothic before. How could it not be, considering their surroundings? Yet, at the same time, for the same reason, their music was accessible, strangely familiar, utterly digestible. It is the living embodiment of where they came from, a strange territory that doesn’t get nearly enough credit and is burdened by some dark aura.

This Music Leaves Stains

This Music Leaves Stains